About Me

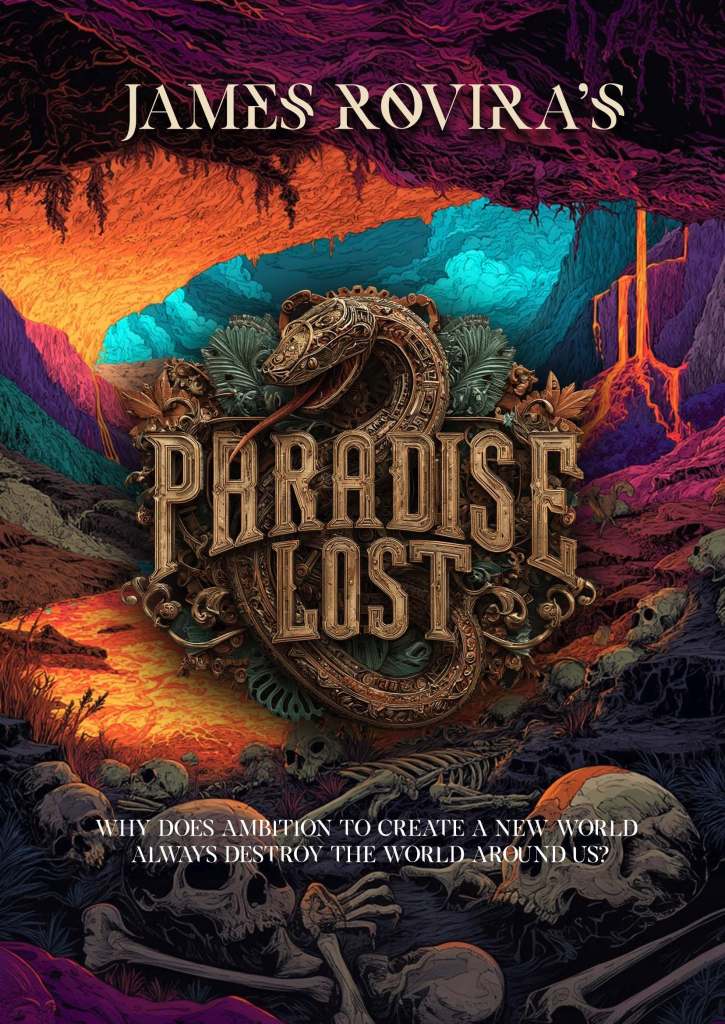

James Rovira is a scholar of British Romanticism and Continental Philosophy, a writer, editor, and literary agent whose most recent work is Paradise Lost.

Contact Me

Pages

- Chapter 1, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 10, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 11, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 2, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 3, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 4, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 5, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 6, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 7, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 8, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Chapter 9, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Creative

- Encoding and Decoding William Blake

- Errata, Blake and Kierkegaard: Creation and Anxiety

- Errata: Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Main Site Categories

- Preface and Introduction, Rock and Romanticism, Lexington Books

- Rock and Romanticism: Blake, Wordsworth, and Rock from Dylan to U2

- Scholarship

- Teaching

- The Bookstore

- The James Rovira Literary Agency

- About

- Blake and Kierkegaard: Creation and Anxiety

- Blake in the Heartland: Online Gallery

- Women in Rock, Women in Romanticism

- Contact

- David Bowie and Romanticism

- The Scars Project

- James Rovira’s CV

The Museum is closed to the public on May 1, June 27, December 24, 25 and 31, 2023, and January 1, 2024.

Admission is free of charge.