The following paper was presented at the 2023 Popular Culture Association Conference of the South in New Orleans in session F 11.1: Friday, September 29th at 4:00 p.m. in Algiers A. Many thanks to Samuel Lyndon Gladden, University of New Orleans, for his work organizing this panel.

By 2015 I’d been living in Ohio for seven years, so I wanted to undertake a project dedicated to the State of Ohio. Given the presence of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, and Cleveland’s legendary status as one of America’s great rock and roll cities, I thought I’d do something dedicated to rock and roll in Ohio. Around that time, I’d visited Best Buy in Columbus, Ohio to buy a camera for my daughter in Florida who was getting ready to start a Digital Media degree at UCF. Two young women spent an hour helping me locate the right equipment at the Best Buy in Ohio and then finding the same equipment in Altamonte Springs, FL, which I could purchase in Ohio to be held at the store in Florida. During the course of our conversation I found out they were both photographers, and one of them, Taylor Fickes, shared with me some of her concert photos. They were so spectacular they gave me the idea for an exhibit dedicated to Ohio rock and roll photography. After speaking with Lee Fearnside, then Director of my campus’s art gallery, we decided to stage photographs of Ohio rock artists for an exhibit titled Rock and Roll in Ohio which ran during the Fall 2016 semester.

I thought I’d design an honors course based on rock music and literature to coincide with the exhibit, so I posted to NASSR-L, a Romanticism listserv, asking for ideas. The response was so overwhelming that I decided to issue a call for papers for chapters in a collection dedicated to rock and roll music and Romanticism. Again, the response was overwhelming: 50 chapter proposals, 26 completed chapters, 25 chapters published in two separate collections: Rock and Romanticism: Blake, Wordsworth, and Rock from Dylan to U2 and Rock and Romanticism: Post-Punk, Goth, and Metal as Dark Romanticisms, both published in 2018. Taylor’s photographs were used for each of the book covers (check them out and you’ll see what I mean). Since then, I’ve been publishing collections exploring the influences, intersections, and identities between rock and roll and Romanticism in further collections: David Bowie and Romanticism and then Women in Rock, Women in Romanticism, both published in 2022. I am currently developing another anthology, Romanticism and Heavy Metal (with Julian Knox), and a monograph, Romantic Satanism and Heavy Metal.

Check out the Bookstore.

These collections have explored the intersections and identities between rock and roll and Romanticism from a number of perspectives: the pastoral and the gothic, gender and women’s issues, and in the David Bowie and Romanticism collection, everything from queer studies to celebrity culture to film and literature to fascism and industrial music to the memento mori tradition: David Bowie and an artful death. This panel is made up of contributors to David Bowie and Romanticism, who are all bringing forward their own new, original research in Bowie. My paper today will build on my chapters in that collection to explore the Bowie albums Station to Station and ★ as deliberately crafted companion pieces, something like bookends on the career of one of contemporary music’s greatest geniuses.

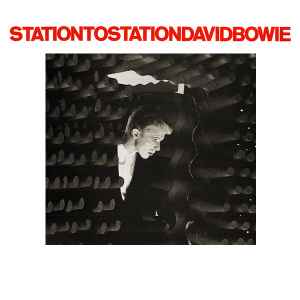

Released in 1976, David Bowie’s Station to Station was remarkably and unexpectedly praised at the time by rock critic Lester Bangs as “an honest attempt by a talented artist to take elements of rock, soul music, and his own idiosyncratic and occasionally pompous showtune / camp predilections and rework this seemingly contradictory melange of styles into something new and powerful. . . I think that Bowie has finally produced his (first) masterpiece.” Station to Station started a remarkable period of innovative music that extended through 1980, covering his so-called Berlin Trilogy albums and ending with Ashes to Ashes. During this period, Bowie reinvented pop and rock music. Released two days before his death and 50 years later, Bowie’s last studio album during his lifetime, ★, similarly reinvented music with a mixture of jazz and rock that defies the boundaries of jazz, rock, or even previously known versions of jazz-rock or jazz fusion. I’ve contributed a chapter about this album’s jazz influences to the forthcoming anthology Jazz and Literature, soon to be published by Routledge.

Released in 1976, David Bowie’s Station to Station was remarkably and unexpectedly praised at the time by rock critic Lester Bangs as “an honest attempt by a talented artist to take elements of rock, soul music, and his own idiosyncratic and occasionally pompous showtune / camp predilections and rework this seemingly contradictory melange of styles into something new and powerful. . . I think that Bowie has finally produced his (first) masterpiece.” Station to Station started a remarkable period of innovative music that extended through 1980, covering his so-called Berlin Trilogy albums and ending with Ashes to Ashes. During this period, Bowie reinvented pop and rock music. Released two days before his death and 50 years later, Bowie’s last studio album during his lifetime, ★, similarly reinvented music with a mixture of jazz and rock that defies the boundaries of jazz, rock, or even previously known versions of jazz-rock or jazz fusion. I’ve contributed a chapter about this album’s jazz influences to the forthcoming anthology Jazz and Literature, soon to be published by Routledge.

Similarities between the two albums, however, run deeper than their shared spirit of innovation. Both albums are about 40 minutes in length, and both albums begin with songs approximately ten minutes long that are similarly composed: two separate melodies spliced together with a brief instrumental interlude that serves as a transition from one half to the next. I would like to suggest that these similarities are not just coincidental. These albums were thematically designed to represent a complete cycle of life and death beginning with the primarily white cover of Station to Station and ending with the completely black album ★. I believe that this trajectory can inform our understanding of Bowie’s own view of the totality of his creative output, one that we will see becomes focused on the character Thomas Jerome Newton.

Similarities between the two albums, however, run deeper than their shared spirit of innovation. Both albums are about 40 minutes in length, and both albums begin with songs approximately ten minutes long that are similarly composed: two separate melodies spliced together with a brief instrumental interlude that serves as a transition from one half to the next. I would like to suggest that these similarities are not just coincidental. These albums were thematically designed to represent a complete cycle of life and death beginning with the primarily white cover of Station to Station and ending with the completely black album ★. I believe that this trajectory can inform our understanding of Bowie’s own view of the totality of his creative output, one that we will see becomes focused on the character Thomas Jerome Newton.

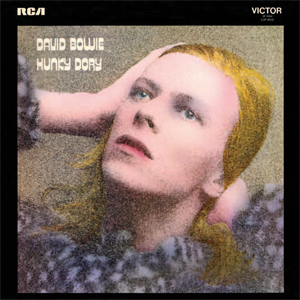

While I’m describing Station to Station and ★ as bookends on Bowie’s career, the trajectory they cover begins with Bowie’s 1970 album The Man Who Sold the World, whose initial UK album cover featured Bowie in long blonde hair wearing a “man dress.” This album was followed by Hunky Dory whose cover features Bowie, still sporting long blonde hair, striking a pose reminiscent of Greta Garbo or Lauren Bacall: oh my God, leave me alone. Bowie’s next album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, emphasizes an alien, sci-fi persona that would remain with him, off and on, until the end of his life. The alien rock star Ziggy Stardust is not so much a departure from Bowie’s sexually ambiguous public personas on his previous two albums as an extension and representation of it: most commentary on Bowie’s work asserts that Bowie’s non-standard sexuality was exactly what made him feel like an alien.

While I’m describing Station to Station and ★ as bookends on Bowie’s career, the trajectory they cover begins with Bowie’s 1970 album The Man Who Sold the World, whose initial UK album cover featured Bowie in long blonde hair wearing a “man dress.” This album was followed by Hunky Dory whose cover features Bowie, still sporting long blonde hair, striking a pose reminiscent of Greta Garbo or Lauren Bacall: oh my God, leave me alone. Bowie’s next album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, emphasizes an alien, sci-fi persona that would remain with him, off and on, until the end of his life. The alien rock star Ziggy Stardust is not so much a departure from Bowie’s sexually ambiguous public personas on his previous two albums as an extension and representation of it: most commentary on Bowie’s work asserts that Bowie’s non-standard sexuality was exactly what made him feel like an alien.

I argue in one of my chapters in David Bowie and Romanticism that Bowie’s 1979 Saturday Night Live performances defined what queerness—Bowie’s non-binary sexuality—may have meant to him at the time. His three performances feature songs from the beginning, middle, and end of the 1970s. While his heavily made-up face and hairstyle remain the same for all three songs, his body changes beneath them. In the first song, Bowie is immobilized within a stiff tuxedo doll costume. His backup singers, both in drag, have to lift him by his hands to place him in front of his microphone. He wears a greenscreen outfit with a male puppet body projected onto it for the third song, but for his second song, he’s dressed in a woman’s business suit. His masculine-gendered performances are stiff or hyperactive but equally unnatural, while during his feminine-gendered performance he looks and moves naturally, like a human being, possibly commenting on the freedom he feels gendered feminine and the restrictions he feels gendered masculine: his socially prescribed sexual identity is too confining for him. But most importantly for my purposes is that his head remains the same in all three songs while his body alternates beneath it from song to song, which is I think the essence of Bowie’s non-binary sexuality, one which could shift identities based upon the object of his desire. I argue in David Bowie and Romanticism that this view of human sexuality has its most immediate origin in Milton’s Paradise Lost and its description of angelic sex, and that this understanding of human sexuality is specifically Romantic. For Bowie’s part, his sexual non-conformity to any known social norms available to him at the time led him to understand himself as an alien.

I argue in one of my chapters in David Bowie and Romanticism that Bowie’s 1979 Saturday Night Live performances defined what queerness—Bowie’s non-binary sexuality—may have meant to him at the time. His three performances feature songs from the beginning, middle, and end of the 1970s. While his heavily made-up face and hairstyle remain the same for all three songs, his body changes beneath them. In the first song, Bowie is immobilized within a stiff tuxedo doll costume. His backup singers, both in drag, have to lift him by his hands to place him in front of his microphone. He wears a greenscreen outfit with a male puppet body projected onto it for the third song, but for his second song, he’s dressed in a woman’s business suit. His masculine-gendered performances are stiff or hyperactive but equally unnatural, while during his feminine-gendered performance he looks and moves naturally, like a human being, possibly commenting on the freedom he feels gendered feminine and the restrictions he feels gendered masculine: his socially prescribed sexual identity is too confining for him. But most importantly for my purposes is that his head remains the same in all three songs while his body alternates beneath it from song to song, which is I think the essence of Bowie’s non-binary sexuality, one which could shift identities based upon the object of his desire. I argue in David Bowie and Romanticism that this view of human sexuality has its most immediate origin in Milton’s Paradise Lost and its description of angelic sex, and that this understanding of human sexuality is specifically Romantic. For Bowie’s part, his sexual non-conformity to any known social norms available to him at the time led him to understand himself as an alien.

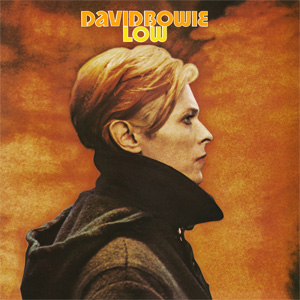

Bowie’s established alien persona was reinforced and capitalized upon in Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth. Bowie’s character, Thomas Jerome Newton, was an alien who traveled to Earth with the intention of returning water to his arid home planet in order to save both his own civilization and his wife and child. He became caught up in Earth politics, wealth, and intrigue so never returned, leaving his family to die of dehydration on his home planet. Bowie revised this character and projected it forward into the future in his 2015 stage play Lazarus, attending opening night about one month before his death in his last public appearance. Bowie didn’t immediately drop Thomas Jerome Newton as one of his characters after the completion of his film even in the 70s, however, appearing as that character on the cover of his next two albums, Station to Station (1976) and Low (1977). Bowie as Newton on the cover of Low appears in profile against an orange sky that evokes Newton’s arid home planet. The cover of Station to Station, on the other hand, is a still from the film depicting Newton stepping back into his spacecraft to return to his home planet, a trip that was never completed.

Bowie’s established alien persona was reinforced and capitalized upon in Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth. Bowie’s character, Thomas Jerome Newton, was an alien who traveled to Earth with the intention of returning water to his arid home planet in order to save both his own civilization and his wife and child. He became caught up in Earth politics, wealth, and intrigue so never returned, leaving his family to die of dehydration on his home planet. Bowie revised this character and projected it forward into the future in his 2015 stage play Lazarus, attending opening night about one month before his death in his last public appearance. Bowie didn’t immediately drop Thomas Jerome Newton as one of his characters after the completion of his film even in the 70s, however, appearing as that character on the cover of his next two albums, Station to Station (1976) and Low (1977). Bowie as Newton on the cover of Low appears in profile against an orange sky that evokes Newton’s arid home planet. The cover of Station to Station, on the other hand, is a still from the film depicting Newton stepping back into his spacecraft to return to his home planet, a trip that was never completed.

Key to the title track of Station to Station is the Sefirot, a Kabbalistic representation of the ten divine emanations through which God channels His being to all creation. Bowie references the Sefirot in these lines from the title track: “Here are we, one magical movement / From Kether to Malkuth / There are you, drive like a demon / From station to station.” “Kether” or Keter is the first of the ten, meaning crown, while Malkuth is the last, meaning kingdom. Kether is the unknowable, unconscious Divine will, while Malkuth is derived only from previous Sefirot and governs the physical world. “Station to station,” according to Bowie in interviews, refers to the stations of the cross despite the opening train sounds inspired by Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn.” Bowie’s lyrics here describe a progress that encompasses all in the interaction between the Thin White Duke and his lover, or the musician and his audience, keeping in mind that the Sefirot are gendered as well. Interestingly, this reference to the Sefirot was carried forward from Bowie’s filming of The Man Who Fell to Earth: it was reported that Bowie often spent time drawing images of the Tree of Sephirot while on set, and the back cover of the 1991 reissue of Station to Station depicts Bowie as Newton, wearing black pants and a black sweater with diagonal white stripes painted across them, sitting on the floor drawing the Sefirot.

Key to the title track of Station to Station is the Sefirot, a Kabbalistic representation of the ten divine emanations through which God channels His being to all creation. Bowie references the Sefirot in these lines from the title track: “Here are we, one magical movement / From Kether to Malkuth / There are you, drive like a demon / From station to station.” “Kether” or Keter is the first of the ten, meaning crown, while Malkuth is the last, meaning kingdom. Kether is the unknowable, unconscious Divine will, while Malkuth is derived only from previous Sefirot and governs the physical world. “Station to station,” according to Bowie in interviews, refers to the stations of the cross despite the opening train sounds inspired by Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn.” Bowie’s lyrics here describe a progress that encompasses all in the interaction between the Thin White Duke and his lover, or the musician and his audience, keeping in mind that the Sefirot are gendered as well. Interestingly, this reference to the Sefirot was carried forward from Bowie’s filming of The Man Who Fell to Earth: it was reported that Bowie often spent time drawing images of the Tree of Sephirot while on set, and the back cover of the 1991 reissue of Station to Station depicts Bowie as Newton, wearing black pants and a black sweater with diagonal white stripes painted across them, sitting on the floor drawing the Sefirot.

While “Station to Station” evokes life, creation, and immanence, the song “Blackstar” evokes death and exile: “Something happened on the day he died / Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside / Somebody else took his place, and bravely cried / I’m a Blackstar.” “Blackstar’s” video continues Bowie’s association with space: set on the moon, or on another world, the jeweled skull of an astronaut is retrieved by a young woman reminiscent of Frida Kahlo in a plain dress. She also has a mouse’s tail. She carries the skull through a village up to a large stone temple at the top of a hill, where it is presented to an African priestess accompanied by a group of young female novitiates while a skeleton, presumably freed from the spacesuit, floats away into space toward a sun in full solar eclipse. During the first musical segment of the video, Bowie has medical gauze wrapped around his head with buttons placed over his eyes, while in the second segment, the gauze comes off, and we see it worn by living scarecrows in a cornfield. Overall, the song is about celebrity facing death, the Blackstar, lifting off and being replaced by the next celebrity.

While “Station to Station” evokes life, creation, and immanence, the song “Blackstar” evokes death and exile: “Something happened on the day he died / Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside / Somebody else took his place, and bravely cried / I’m a Blackstar.” “Blackstar’s” video continues Bowie’s association with space: set on the moon, or on another world, the jeweled skull of an astronaut is retrieved by a young woman reminiscent of Frida Kahlo in a plain dress. She also has a mouse’s tail. She carries the skull through a village up to a large stone temple at the top of a hill, where it is presented to an African priestess accompanied by a group of young female novitiates while a skeleton, presumably freed from the spacesuit, floats away into space toward a sun in full solar eclipse. During the first musical segment of the video, Bowie has medical gauze wrapped around his head with buttons placed over his eyes, while in the second segment, the gauze comes off, and we see it worn by living scarecrows in a cornfield. Overall, the song is about celebrity facing death, the Blackstar, lifting off and being replaced by the next celebrity.

But the song is visually and lyrically connected to “Lazarus,” Bowie’s next single and video for the album. The lyrics again seem to describe a celebrity in “Heaven,” which is New York City, anticipating his freedom. In the video, the Lazarus character is lying in a hospital bed with the same gauze wrapped around his head and the same buttons over his eyes. He is gradually lifting off while one of the women from the “Blackstar” video is lying under his bed reaching up, presumably, to stop his ascent. These videos appear to be companion pieces, “Lazarus” presenting the moments leading up to the artist’s death from the dying artist’s point of view—Bowie is pictured sitting and writing during this video—while “Blackstar” presents the artist’s landing and assimilation into the next world after death. But most interesting of all, at the end of “Lazarus” Bowie disappears into a cabinet, and he’s wearing the same clothing that appears on the back of the 1991 reissue of Station to Station, black pants and a sweater with diagonal white stripes painted across them, the outfit in which he was drawing a Tree of Sefirot on the floor.

But the song is visually and lyrically connected to “Lazarus,” Bowie’s next single and video for the album. The lyrics again seem to describe a celebrity in “Heaven,” which is New York City, anticipating his freedom. In the video, the Lazarus character is lying in a hospital bed with the same gauze wrapped around his head and the same buttons over his eyes. He is gradually lifting off while one of the women from the “Blackstar” video is lying under his bed reaching up, presumably, to stop his ascent. These videos appear to be companion pieces, “Lazarus” presenting the moments leading up to the artist’s death from the dying artist’s point of view—Bowie is pictured sitting and writing during this video—while “Blackstar” presents the artist’s landing and assimilation into the next world after death. But most interesting of all, at the end of “Lazarus” Bowie disappears into a cabinet, and he’s wearing the same clothing that appears on the back of the 1991 reissue of Station to Station, black pants and a sweater with diagonal white stripes painted across them, the outfit in which he was drawing a Tree of Sefirot on the floor.

These connections tempt me into constructing a narrative: “Station to Station” captures the moment of the alien’s return home, but that return is aborted: he crashes on the moon and dies, never coming home. “Lazarus” captures the moment of departure from this life from the celebrity’s perspective, while “Blackstar” is the assimilation of his remains after death into an otherworldly environment: he has returned home. While the video for “Blackstar” continues Bowie’s use of space imagery, the album booklet’s gloss black artwork on a matte black background reinforces Bowie’s space imagery, such as segments of lyrics being connected like constellations, the graphic attached to the Voyager spacecraft appearing above the lyrics for “Girl Loves Me,” and the inside cover behind the cutout star revealing constellations when held up to the light. Since Bowie’s stage play Lazarus continues the story of Thomas Jerome Newton, I think Bowie viewed The Man Who Fell to Earth and its central character as an analogue for his own life as a celebrity: he always felt out of place, an alien of sorts, and was always searching for home. Only the women in his life who received him, especially Iman, his own African priestess, came close to giving him that home, but only by finally receiving his remains.

Leave a comment