[Reposted from 2017.]

[Reposted from 2017.]

Artists and their Art

My two points of reference for artists and their creations here will be New York Stories and Bullets Over Broadway, both excellent films that in their own ways comment on the art of filmmaking and creativity. I won’t be discussing it now, but I’d also recommend the film S.O.B.

New York Stories is an anthology film featuring three short films, one each by Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Woody Allen. Scorsese’s and Coppola’s films aren’t at all characteristic of their usual work and are wonderful, magical, and worth watching. Allen’s contribution is a hilarious abstract of his entire life’s work. If you can pick up or stream these films, don’t pass them by.

Scorcese’s short, Life Lessons, is about New York artist Lionel Dobie (perf. Nick Nolte) and his much younger live-in protégé and lover Paulette (perf. Rosanna Arquette) immediately before a big opening for one of Dobie’s shows. They have become estranged but are still living together. Dobie remains sexually obsessed with Paulette, while Paulette continues living with Dobie to be mentored by him and to receive some confidence in and validation of her work as an artist.

He continually withholds his praise, however, always coming back to, “Well, what do you think?”, which increasingly frustrates her. She, in turn, teases him sexually almost to the point of torture while still withholding herself from him, largely as punishment for his refusal to validate her work. I think she would have been happy even with a clear invalidation, for that matter — so that she could know she was wasting her time with art and move on with her life. But she didn’t get anything from Dobie either way. This dysfunctional dynamic, combined with how difficult it is to live with Dobie (he can only paint with his music on at almost concert level volumes), ultimately drives her away in a rage right before his show.

But what’s particularly interesting about the film is its depiction of the artistic process. The more tense, dysfunctional, and intense this relationship became, the better Dobie was able to paint. Her screaming and their shared frustration seemed to fuel him creatively. On the night of the show, he attends alone, and at the end we see him recruit a new young female protégé, one clearly hoping to be mentored by him, and for his part clearly intended to serve as his perverse inspiration for his next project.

Now keep this picture in mind while I move on to the next film: Bullets Over  Broadway. Bullets is about young, idealistic playwright David Shayne (perf. John Cusack) who’s seeking fame with marginal talent. He cuts a deal with a mob boss to get financing for his play: in exchange for financing, the play will star the mob boss’s girlfriend, Olive Neal (perf. Jennifer Tilly). To keep her safe and to make sure that David lives up to his end of the bargain, the boss assigns hitman Cheech (perf. Chaz Palminteri) to attend rehearsals.

Broadway. Bullets is about young, idealistic playwright David Shayne (perf. John Cusack) who’s seeking fame with marginal talent. He cuts a deal with a mob boss to get financing for his play: in exchange for financing, the play will star the mob boss’s girlfriend, Olive Neal (perf. Jennifer Tilly). To keep her safe and to make sure that David lives up to his end of the bargain, the boss assigns hitman Cheech (perf. Chaz Palminteri) to attend rehearsals.

In the course of rehearsing the play, however, David’s bad writing is confronted by the professional actors he hired. Cheech, sitting in the position of the audience and the critic, virtually rewrites the play with David as it is being rehearsed: Cheech has a talent for character, narrative, pacing, and lines that David doesn’t. In short, Cheech is a real writer in ways that David is not.

When the play goes to performance, it is universally praised, with the exception of Olive’s acting. Olive is not only a bad actress but something of an idiot. So Cheech does what needs to be done: he drives her out to the docks and shoots her, dumping her body in the water. Olive’s part is then played by a professional actress and the play goes on to be widely acclaimed and to a national tour.

What I’d like us to consider here are two characteristics of the artist beyond talent:

1. You’re willing to kill for your work. Short of that, you’re certainly willing to do anything else. It’s the work that matters.

2. What you think about your work is what matters. You know that because you’re the artist. You may listen to others, but in the end, it’s what you think that matters.

Now, you’re reading this post to learn how to develop your creativity. I have two questions for you:

1. Are you willing to kill for your work? What are you really willing to do to create something great? For anyone with any kind of moral compass, the answer is always “No, I’d never kill anyone,” so let me follow up with another question: If it really came down to it, would you at least be seriously tempted?

2. Do you think external validation for your work is irrelevant, at least while you are creating it?

If you don’t answer “Yes” to both of those questions, you’re not really an artist yet, and your creativity will be hampered. You’re in the position of Paulette, who wants to please an audience and get praised for it (in this case, Dobie), or David, who wants to get famous. But you’re not focused on the work itself. You’re focused on drawing external resources inward (which is narcissism) instead of projecting internal resources outward (which is creativity).

Both films affirm this answer in their own ways. Dobie’s refusal to validate or invalidate Paulette’s work was actually the best thing for her, the thing most likely to transform her into an artist. Asking, “What do you think?” directed her to the only question that matters, at least during the creative process. He was trying to get her to fall back upon her own resources, to exercise her own critical judgment of her own work, to act and think like she knew what she was doing.

Everyone wants a great review: don’t get me wrong. But while you’re creating, what you think is what matters. Getting feedback on the finished product — if the feedback is professional, good, and focused on your intent for your work — that helps too. But in the end, it’s what you think that really matters. But do you know what needs to matter even more than your opinion of the work? More than anything else, in fact, even more than you yourself? The work.

Not your reputation, your praise, your recognition, your self-image as an artist, your theory of art, your ideals about art, or the politics or beliefs underlying your art: just the work itself. That’s why Scorsese’s representation of the true artist was of someone willing to kill to perfect his play. It was easy for him because he was a hitman, but I think the artist part of him would have been just as willing to kill himself for his work if, somehow, that is what it took to perfect it. At least in theory: in reality, that’s never the case. Suicides for art are generally committed by pseudo-artists seeking fame.

If you know what it’s like to selflessly love your children, I think you know what I’m talking about, but I only say that with the caveat that to develop as an artist you need to understand that your work really isn’t your baby. That means you’re willing to sacrifice anything within the work itself to perfect the work. The real killing takes place during the creative process, a sacrifice made within the creative work itself.

Creativity vs. Narcissism

Next, I’d like to return to the idea that creativity is the act of projecting internal resources outward. It’s not unusual, of course, to see an artist’s work as a representation of his or her experiences. Perhaps the best statement to this effect is Wordsworth’s 1800 Preface to Lyrical Ballads. But that’s only partly what I’m talking about.

Next, I’d like to return to the idea that creativity is the act of projecting internal resources outward. It’s not unusual, of course, to see an artist’s work as a representation of his or her experiences. Perhaps the best statement to this effect is Wordsworth’s 1800 Preface to Lyrical Ballads. But that’s only partly what I’m talking about.

What I really mean to allude to here is the artist’s management of emotional resources to create art (also the subject of Wordsworth’s Preface, by the way). When you create anything, you’re usually going to have to tap in to some reserve of emotional resources that allows you to create, or to some defining experience that has somehow created the person that you are, or to a compelling emotional need. Whatever that emotional core is, you will draw from it to create, and your creations will somehow be reflective of that emotional core.

Now I’m not talking about “writing what you know,” and I’m not claiming that all art is autobiographical. That is dealing with art in the realm of fact: character, plot, setting, etc. Content is interchangeable: the emotional core of a work is what I’m talking about. What makes Stephen King keep writing horror? What makes Nicholas Sparks keep writing romance? Why did Zane Grey focus on adventure and the west? In each case, the author’s creativity comes from some kind of inner emotional core, but that emotion varies widely by artist. It may be fear in some people, anger in others, romantic love in others, sex in others, or depression, or joy, or politics, or God, or just one specific woman or man… all of these result in very different creative products.

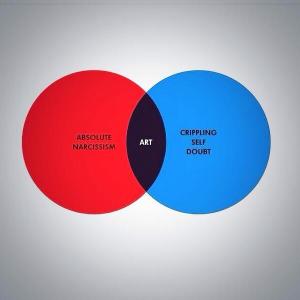

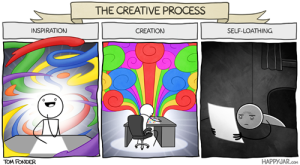

Now I’d like to add a caveat here: not everyone writes like this. Some writers (let’s just talk about writers for now) — and these are among the most productive professionals — see writing as a bag of tricks that they can manipulate expertly to any effect. But this meme  here exists for a reason: talking about your art is a seemingly narcissistic enterprise. That’s why I started this post with a longish discussion of two films. It’s too easy to spend too much time talking about yourself when writing about the subject of creativity.

here exists for a reason: talking about your art is a seemingly narcissistic enterprise. That’s why I started this post with a longish discussion of two films. It’s too easy to spend too much time talking about yourself when writing about the subject of creativity.

When I am able to write something, I have to manipulate emotional material. And that emotional material has to be linked to a word, an idea, or an image. But once I have distinct emotional material linked to a distinct image or word or line, I can write. I usually think next of poetic form — which poetic form is best suited to this content — and then I write.

Art and Its Sources

My history of creative writing began in a small way in high school, but in a much bigger way in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when I started publishing poetry. And then I started graduate school in 1999, and my creative writing stopped almost completely. Around 2009 I started teaching college sophomore-level creative writing classes, so I started writing again, and then in 2014 I hit some inspiration yet again and started writing poetry much more prolifically than I had in the past. In every period in which I wrote, I found some emotional content, latched onto it consciously and deliberately, found words for it, and wrote. But I’d like you to consider the variety of emotional content that we experience every day: it ranges from deep, long-term commitments to fleeting thoughts. However, when you turn any of those into a creative work, they all develop the same profile: they seem big and important.

That’s just not always the case subjectively, though. On more than one occasion during these writing spurts, I’ve had people close to me ask me some specific questions about my personal life because of the poems I’ve written. Are you okay? Need to talk? Alright, who is she? I totally understand that: the questions always reveal the insights of a friend who knows me. And if every poem that I wrote had the same emotional profile, particularly the one implied by the poem, I would need friends asking those questions.

That’s just not always the case subjectively, though. On more than one occasion during these writing spurts, I’ve had people close to me ask me some specific questions about my personal life because of the poems I’ve written. Are you okay? Need to talk? Alright, who is she? I totally understand that: the questions always reveal the insights of a friend who knows me. And if every poem that I wrote had the same emotional profile, particularly the one implied by the poem, I would need friends asking those questions.

Furthermore — and here we’re getting into territory that helps us interpret as well as create art — whenever I grab an emotion and turn it into a poem it becomes something else. Whatever the emotion was that I first relied upon to create is transformed in the creative process, so that the emotion communicated through the work is in somewhat different form than the emotion communicated by the finished work. T.S. Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent” has become for me, therefore, more than a significant theoretical work from the early twentieth century. I now understand it as a personal statement with some applicability to me.

So, you’ve read this far: very far. I think you deserve to have it all boiled down to a few bullet points. So here you go. If you want to create,

- Care about the work itself above all else.

- As a corollary:

- Forget about yourself: think only about the work.

- Forget about being a writer or artist. Focus on writing or creating art.

- Forget about being creative. Focus on creating.

- Forget about what other people think. What does the work do for you?

- And forget that self-conscious assumption that your work is bad, which is always just fear of rejection. I’m going to break up with him/her before s/he breaks up with me.

- Do whatever it takes to grab that emotion that will allow you to create.

- But don’t be a sociopath. People are always more important than things: “Every thing that lives is holy.”

- Create. If you want to be creative, create.

I’d like to conclude by spelling out an unspoken assumption that’s been guiding my thoughts so far. You actually need to know something about your art. You need to know its history, master its conventions, understand the theories behind it. I’ve been able to refer to a couple of texts about creativity here only because I’ve read them. You need to train your knowledge of your art academically. By “academically” I don’t necessarily mean for college credit, but by studying the field systematically. And you need to train or develop your taste. If you don’t develop your taste, you’ll be one of the worst kinds of artists: you will believe that only your own opinion about the work matters, and your opinion will suck. You’ll be an idiot about your own work. Good luck with that.

I’d like to conclude by spelling out an unspoken assumption that’s been guiding my thoughts so far. You actually need to know something about your art. You need to know its history, master its conventions, understand the theories behind it. I’ve been able to refer to a couple of texts about creativity here only because I’ve read them. You need to train your knowledge of your art academically. By “academically” I don’t necessarily mean for college credit, but by studying the field systematically. And you need to train or develop your taste. If you don’t develop your taste, you’ll be one of the worst kinds of artists: you will believe that only your own opinion about the work matters, and your opinion will suck. You’ll be an idiot about your own work. Good luck with that.

Final bit of advice: quit thinking about being creative. Quit studying being creative. Quit reading about being creative. Go out and create something. Above all else, quit being such a coward. Create. Become a god.

An interesting thesis. Clearly, this does not take account of every act of creativity: i.e. both Swift and Dickens ‘improved’ their work by modifying it (e.g. Gulliver’s Travels and Bleak House) in order to give them currency and meet/confront contemporary tastes. So, the will to create/control is sometimes porous and can embrace mimetic socio-economic drivers (the created artefact made malleable). Does this mean that satirists have another dynamic for their creativity. Otherwise, William Blake (claimed as a regal satirist) gave the ‘excess’ of his talent to ‘Devourers’ establishing an antagonistic economy between the consumer and producer of art. Blake, the great systematiser, explored the boundaries of perception or, as has been suggested, of apperception. This would indicate a pristine example of the form of creativity outlined in the blog, but it should be noted that Blake suggested that Milton was not creative/productive in the same way as himself. I think it likely that there are competing forms of creativity and drivers that are intellectual and emotional entangled to different degrees. It may also mean that editorial creativity and conceptual creativity are different again: i.e. Wordsworth’s 1805 Prelude v more Tory leaning later editions that neutralise the radicalism of the earlier version can hardly be conceptualised as the spontaneous overflow claimed for Lyrical Ballads et al.

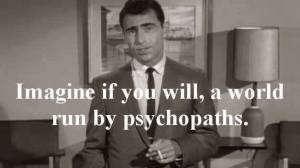

Nonetheless, the idea of dysfunctionality as a source of creativity (psychopathic or sociopathic?) resonates: Nicholson’s Joker in the Batman film embodies such an intense (post)modernist extravagance that echoes Bacon and some of the happenings of the 60s (derived from Surrealists?). Perhaps the nature of creativity is thorny because it is never conceptualised in a vacuum?

LikeLike

Thanks for responding, David. No, even within my post, I say that I’m not taking into account every act of creativity: following Plato’s Ion, I at least distinguish between art as inspiration (manipulation of emotional resources) and art as a skill (creative writers who have a bag of tricks that they manipulate to a deliberate effect). But I like your extension of the discussion into other forms of creativity: editorial creativity, socioeconomic drivers, etc.

However, I think there’s a bit of a misreading of my blog. I don’t mean to identify psycho-(or socio-)pathology as a source of creativity. I distinguish first between art as skill and art as emotional self-expression, and then I affirm the difference of many different types of emotional self-expression:

We might distinguish between the author’s ideal for the work and his or her concessions to economics or audience, but I don’t think we have to: the “concessions” are part of the creative process too, I agree.

The point I mean to make about psychopathology (and yes, perhaps sociopathology is better) is that it attends the creative product. It’s the source of — or perhaps the product of — the monomaniacal focus on the work itself that makes the “true” artist. So creativity has its sources, whatever they may be (and a taxonomy of these sources would make a great book), but being psychopathic clears the ground, so to speak, for the fullest and purest expression of our creativity. It’s like the Dennis Rodman of the soul playing D and getting rebounds so that our creativity can really score.

LikeLike

So, some form of emotional dysfunctional nexus acts like sand in the oyster to create a ‘pearl’? More pertinent is the possibility, then, that the source/outcome of creativity that you identify could be the brand of obsessiveness that drives most (if not all) academics and scholars. It might go some way to explaining why there are some very good researchers who struggle when it comes to empathising with the needs of others (i.e. students) as their lives can become singularities totally focused on their subject and discipline. It would be worth trying to evaluate whether there is any correlation between the quality of output, the mode of creative thought and activity, and the level of obsession.

LikeLike

OH I think the sand in the oyster analogy puts psychopathology too close to the origin of the creative process. Imagine the grain of sand is some kind of emotional core: say the individual’s primary emotion is, or is related to, anger, rage, fear, love, sexual desire, romantic love, nature, etc.

Now for SOME artists — not all (as you previously pointed out), and perhaps only in an idealized sense for the rest of us — the purpose of the creative work is to give some kind of pure expression to that emotional core within the individual work. So the grain of sand in the oyster is a feeling.

BUT what becomes psychopathological is the commitment of the artist to see to it that this emotional content is realized in the most perfect artistic expression possible. So the grain of sand (emotional core) is one thing, the pearl being created around it (artwork expressing the emotional core) is another, and the psychopathology a third thing — the obsessive part of the artist that is totally focused on the pearl and on perfecting it as it is coming into being.

So of course I think your comparison to scholarship and how some scholars think and work is spot on. This series of interrelationships apply to all fields in which something is being created: academic work, engineering, theoretical sciences, and what we normally think of as creative expression — the arts.

LikeLike

Creativity cannot be taught, only facilitated. If you are not innately creative, you never will be no matter how much anyone tries to teach you. Fortunately, most of us are creative; we just need to have our creativity facilitated. There is no standard procedure for this because everybody is creatively different. So facilitation of creativity amounts to non-binding advice based on experience and intuition, wrapped in encouragement and delivered without prejudicial emphasis.

LikeLike

I think I agree with most of that, jaboz55. The purpose of my post is to teach people how to facilitate their own creativity.

I will say, though, that sometimes people need to be pushed, need to have their butts kicked, etc. Sometimes you never know just how creative you can be until you’re facing a deadline with real consequences for missing it. Professionals live with this all of the time.

LikeLike

Dude, you scare me. Also, how do you have time for this blog? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What’s really scary are the artists who think this way and DON’T say it out loud :).

My choice today was blog or grade.

LikeLike